In this post, I will review two Italian crime shows on Netflix, Suburra: Blood on Rome and Gomorrah. Then I tell the story of El Lupo.

Crime Show Reviews

I finished watched Suburra: Blood on Rome a few weeks ago. It’s a crime show about three young men in Rome who are trying to make their way in an organized crime world dominated by a cunning and cold blooded puppetmaster: the aging godfather Samurai. Suburra succeeds in developing characters that despite their shortcomings, I found myself sympathetic towards. The series aptly conveys how organized crime preys on people’s faults, their petty ambitions, greed and desire to be someone important, and draws them into its sinister web. I loved the setting: most of the scenes took place in the darkened streets of the Italian capital and in dingy cafes and gas stations in run down suburbs, but also included shots of the beach at Ostia as well as a gypsy crime family’s ostentatious palace. What I also liked about Suburra was that the way the show concluded was completely unexpected. Watch it, but beware, it is dark, intense and sometimes violent and if you’re a devout Catholic, you may not appreciate the opening scene. Also, it includes some really awful men’s hairstyles.

Gomorrah is another Italian crime series, set in Napoli, and its subject is the crime family and organization of one of the city’s infamous camorra kingpins. The show takes its name from a movie that came out a few years ago, but the show focuses on one main storyline. The film Gomorrah is incredibly bleak and depressing, delving the darkest of subjects: illegal toxic waste dumping, the exploitation of child and immigrant labor and Europe’s largest open-air drug market, Napoli’s infamous, decaying Scampia housing projects. Much of Gomorrah takes place in this dystopian wasteland, which is Europe’s answer to the now "revitalized" Cabrini Green Projects in Chicago. Some episodes of Gomorrah can be very violent, but the series portrays its characters in a very human way. I haven’t finished the show but so far, I would recommend it. It is, like Suburra and nearly every crime drama I’ve watched, dark and intense, so if you’ve had a rough day and need something light, you might want to check out season two of Aziz Ansari’s Master of None, which also takes place in Italy.

Here I try to be clever and transition into talking about my cool travel story

I have always been fascinated with mafia crime movies and TV series, but especially so after having spent some time in Sicily, the birthplace of the la cosa nostra, one of the world’s most infamous crime organizations. I went to Sicily in the summer of 2001, after my first year of college at Stanford. As a freshman, I was required to take IHUM – Introduction to the Humanities –and I ended up in an excellent two quarter series called Ancient Empires. The first quarter we studied Greece and the second, Rome. The professor who taught the Greece portion ran an archaeological excavation in Sicily and was recruiting students to come work for a few weeks in the summer. I jumped at the chance, and not long after spring quarter finals, I was on a plane to Palermo.

Palermo’s airport is one of the more dangerous and spectacular in the world, its runway sandwiched between steep limestone cliffs and the sparkling waters of the Mediterranean Sea. However, despite the dramatic scenery, the first thing that caught my attention after one of the project staff picked me up was a drum full of burning trash on the side of the highway. Thus, began my experience in Sicily.

Most of my time on that intriguing island I spent laboring away at an archaeological site called Monte Polizzo, located on the shadeless summit of a mountain in Western Sicily. Most of the archaeological work involved chipping away hardened earth with a pickaxe (in Sicily, like California, summers are very dry), and finding pieces of rough, broken pottery, then switching to a smaller pickaxe to dig up the pottery. I found no coins, no swords, no tunnel that led to an undiscovered crypt full of jewels and mummies. Just dust and pottery and more dust, and the scorching Sicilian sun.

When we weren’t working, we eagerly consumed the endless supply of local wine at the excavation house, or ate delicious gelato at one of the many gelaterias along the main street of Salemi, the sleepy hill town nearby. We explored the local beaches, and swam in the azure waters of the Mediterranean, which were so warm and salty you could float around in them forever. One afternoon, we visited the labyrinthine casbah of Mazara del Vallo, a nearby port city, and found a hookah bar where we relaxed for a couple hours (Sicily was ruled by Arabs for over 200 years, ending around 1100 AD). And we ate: Sicilian food is an incredible mélange of all of the empires that have ruled the island: Greek, Roman, Arab, Norman, Spanish, Italian. One of the most unique Sicilian dishes is pasta alla sarde, made with fennel, pine nuts, currants, sardines and anchovies.

We also played soccer and basketball games against the local teams in Salemi. Our American style hoops were too rough for the oversensitive European refs, and we lost to the Salemi team, much to the joy of their coach. The Salemi team’s coach was a man named Baldo, an enthusiastic, balding man barely 5 ft. tall, a pharmaceutical salesman who often visited the excavation house, especially when we hosted parties. He was a sort of liaison between the town and the project, though no one ever really understood what his role exactly was.

Baldo appeared at one Friday night party, and we became friends. Despite the language barrier—I was learning Italian but it was sparse at that point—he thought I was quite funny. I remember being drunk at that party, as I often was during my free time at that point in my life. After observing me scoping out and trying to flirt with the female party guests, Baldo coined a nickname for me: El Lupo, the wolf. For the weeks to come, he would come by the excavation house, find me, laugh and repeat my nickname, El Lupo. It brought him endless amusement.

A few weeks later, at another party, Baldo pulled me aside and told me in his heavily accented English: “tomorrow, we go Corleone.” Corleone is a provincial hill town located about an hour east of Salemi; here in the United States, Corleone is famous of course because of the Godfather films (if you didn’t know this, please call in sick tomorrow and watch Godfather I and II). However, the real kingpin to emerge from that impoverished locale in Western Sicily was Toto Riina, a mobster who died just a few days ago at age 87. Despite suffering from various incurable diseases, he was kept in prison until his last days due to the unthinkably brutal nature of the crimes he’d committed. He was capo de tutti capi: the boss of the bosses, and if you were out of line, he’d have you dissolving in a barrel of hydrochloric acid before you could finish your café corretto. Riina was responsible for hundreds of killings in Italy, including the 1992 deaths of two anti-mafia magistrates, Falcone and Borsellino.

The next morning, I waited for Baldo to take us to Corleone along with two other members of the excavation who were brave enough to join the adventure. Given his propensity to constantly joke, and my intoxicated state the previous night, I wasn’t completely sure if Baldo was actually going to come. But he showed up in his tiny car and I sat in the front with my pocket Italian dictionary, trying to figure out what was going on. It didn’t take long to reach Corleone, a nondescript town with beige colored three and four-story apartment buildings, narrow streets with traffic and honking cars, various people yelling and cafés with old men eating pastries and sipping espresso. In Corleone, we visited some museums and churches, then Baldo drove through a more run-down section of town he referred to as “Bronx of Corleone” before taking us back to Salemi.

Despite its fame as the birthplace of ruthless criminals, Corleone wasn’t all that exciting, but with Baldo as our guide, our visit there was one of the most memorable day trips that summer on the island. Sicily has an incalculably rich treasure trove of historic sites, and I was lucky enough to visit the magnificent Greek temples of Agrigento and Selinunte and the Greek Amphitheatre at Segesta. Equally breathtaking was the Arab-Norman Cathedral at Monreale and the ornate, yet neglected Baroque facades in the old city of Palermo. I loved Sicily’s chaotic capital, especially Palermo’s street markets. The markets were smelly, loud, and crowded; stands with tables piled high with seafood, meats and fruits that filled the tiny, winding streets of the decrepit old city.

When I returned to California, the sights, smells and sounds of Sicily remained vivid in my memory and I immediately began plotting my return to that island in the Mediterranean. I imagined meeting a beautiful woman and spending my summer nights strolling down the streets of one of the island’s seaside towns, which were so full of life in the evenings. This fantasy, of traveling to a faraway land and becoming a different person, had a strong appeal to me at that time in my life. At age 19, I found myself having to make enormous decisions that would determine the course of my life and the expectations that everyone had of me as this perfect, model student. Like many 19 year olds, I was certainly not a model of responsibility: I chose to escape, whether it was through shots of gin before a party or by seeking adventures in distant lands. I returned to Sicily the following summer to work on the archaeological excavation at Monte Polizzo again. After that I studied abroad in Turkey for a year, and then worked on another dig. Eventually and reluctantly, I returned to the US to finish my degree.

Afterword

It’s easy to tell stories about travel and to write about it too. Travel is exciting, and fun, and full of new sensory experiences to describe to all who will listen. But just as I found out when I returned from Sicily and then from Turkey, most people don’t want to hear about how awesome it was to eat pizza on the piazza in Napoli; or swim through a sea cave in the Mediterranean, or about how this funny, short Sicilian guy named Baldo started calling me El Lupo and then took us on a trip to Corleone. Being able to travel is an enormous privilege. Even though returning home can be painfully isolating and dislocating, if I had enough vacation days saved up at work, I would travel in a second. Maybe not to Corleone though.

Going forward, I want to put together a longer piece out of shorter posts I did a few years ago while I was working at a rice farm. I did some of my best writing during that time and it was a challenging and illuminating experience that I still think about a lot. I also want to continue to improve as a writer, and am looking into taking some classes. Writing has always been very important to me and I want to see where I can go with it during this time of transition in my life. Thanks to everyone who has been reading, please leave a comment and keep in touch.

Crime Show Reviews

I finished watched Suburra: Blood on Rome a few weeks ago. It’s a crime show about three young men in Rome who are trying to make their way in an organized crime world dominated by a cunning and cold blooded puppetmaster: the aging godfather Samurai. Suburra succeeds in developing characters that despite their shortcomings, I found myself sympathetic towards. The series aptly conveys how organized crime preys on people’s faults, their petty ambitions, greed and desire to be someone important, and draws them into its sinister web. I loved the setting: most of the scenes took place in the darkened streets of the Italian capital and in dingy cafes and gas stations in run down suburbs, but also included shots of the beach at Ostia as well as a gypsy crime family’s ostentatious palace. What I also liked about Suburra was that the way the show concluded was completely unexpected. Watch it, but beware, it is dark, intense and sometimes violent and if you’re a devout Catholic, you may not appreciate the opening scene. Also, it includes some really awful men’s hairstyles.

Gomorrah is another Italian crime series, set in Napoli, and its subject is the crime family and organization of one of the city’s infamous camorra kingpins. The show takes its name from a movie that came out a few years ago, but the show focuses on one main storyline. The film Gomorrah is incredibly bleak and depressing, delving the darkest of subjects: illegal toxic waste dumping, the exploitation of child and immigrant labor and Europe’s largest open-air drug market, Napoli’s infamous, decaying Scampia housing projects. Much of Gomorrah takes place in this dystopian wasteland, which is Europe’s answer to the now "revitalized" Cabrini Green Projects in Chicago. Some episodes of Gomorrah can be very violent, but the series portrays its characters in a very human way. I haven’t finished the show but so far, I would recommend it. It is, like Suburra and nearly every crime drama I’ve watched, dark and intense, so if you’ve had a rough day and need something light, you might want to check out season two of Aziz Ansari’s Master of None, which also takes place in Italy.

Here I try to be clever and transition into talking about my cool travel story

I have always been fascinated with mafia crime movies and TV series, but especially so after having spent some time in Sicily, the birthplace of the la cosa nostra, one of the world’s most infamous crime organizations. I went to Sicily in the summer of 2001, after my first year of college at Stanford. As a freshman, I was required to take IHUM – Introduction to the Humanities –and I ended up in an excellent two quarter series called Ancient Empires. The first quarter we studied Greece and the second, Rome. The professor who taught the Greece portion ran an archaeological excavation in Sicily and was recruiting students to come work for a few weeks in the summer. I jumped at the chance, and not long after spring quarter finals, I was on a plane to Palermo.

Palermo’s airport is one of the more dangerous and spectacular in the world, its runway sandwiched between steep limestone cliffs and the sparkling waters of the Mediterranean Sea. However, despite the dramatic scenery, the first thing that caught my attention after one of the project staff picked me up was a drum full of burning trash on the side of the highway. Thus, began my experience in Sicily.

|

| Sicilian Coast |

Most of my time on that intriguing island I spent laboring away at an archaeological site called Monte Polizzo, located on the shadeless summit of a mountain in Western Sicily. Most of the archaeological work involved chipping away hardened earth with a pickaxe (in Sicily, like California, summers are very dry), and finding pieces of rough, broken pottery, then switching to a smaller pickaxe to dig up the pottery. I found no coins, no swords, no tunnel that led to an undiscovered crypt full of jewels and mummies. Just dust and pottery and more dust, and the scorching Sicilian sun.

|

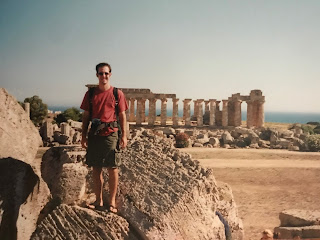

| Greek Ruins at Selinunte |

When we weren’t working, we eagerly consumed the endless supply of local wine at the excavation house, or ate delicious gelato at one of the many gelaterias along the main street of Salemi, the sleepy hill town nearby. We explored the local beaches, and swam in the azure waters of the Mediterranean, which were so warm and salty you could float around in them forever. One afternoon, we visited the labyrinthine casbah of Mazara del Vallo, a nearby port city, and found a hookah bar where we relaxed for a couple hours (Sicily was ruled by Arabs for over 200 years, ending around 1100 AD). And we ate: Sicilian food is an incredible mélange of all of the empires that have ruled the island: Greek, Roman, Arab, Norman, Spanish, Italian. One of the most unique Sicilian dishes is pasta alla sarde, made with fennel, pine nuts, currants, sardines and anchovies.

|

| Castellamare del Golfo |

We also played soccer and basketball games against the local teams in Salemi. Our American style hoops were too rough for the oversensitive European refs, and we lost to the Salemi team, much to the joy of their coach. The Salemi team’s coach was a man named Baldo, an enthusiastic, balding man barely 5 ft. tall, a pharmaceutical salesman who often visited the excavation house, especially when we hosted parties. He was a sort of liaison between the town and the project, though no one ever really understood what his role exactly was.

Baldo appeared at one Friday night party, and we became friends. Despite the language barrier—I was learning Italian but it was sparse at that point—he thought I was quite funny. I remember being drunk at that party, as I often was during my free time at that point in my life. After observing me scoping out and trying to flirt with the female party guests, Baldo coined a nickname for me: El Lupo, the wolf. For the weeks to come, he would come by the excavation house, find me, laugh and repeat my nickname, El Lupo. It brought him endless amusement.

|

| Old City, Salemi |

A few weeks later, at another party, Baldo pulled me aside and told me in his heavily accented English: “tomorrow, we go Corleone.” Corleone is a provincial hill town located about an hour east of Salemi; here in the United States, Corleone is famous of course because of the Godfather films (if you didn’t know this, please call in sick tomorrow and watch Godfather I and II). However, the real kingpin to emerge from that impoverished locale in Western Sicily was Toto Riina, a mobster who died just a few days ago at age 87. Despite suffering from various incurable diseases, he was kept in prison until his last days due to the unthinkably brutal nature of the crimes he’d committed. He was capo de tutti capi: the boss of the bosses, and if you were out of line, he’d have you dissolving in a barrel of hydrochloric acid before you could finish your café corretto. Riina was responsible for hundreds of killings in Italy, including the 1992 deaths of two anti-mafia magistrates, Falcone and Borsellino.

The next morning, I waited for Baldo to take us to Corleone along with two other members of the excavation who were brave enough to join the adventure. Given his propensity to constantly joke, and my intoxicated state the previous night, I wasn’t completely sure if Baldo was actually going to come. But he showed up in his tiny car and I sat in the front with my pocket Italian dictionary, trying to figure out what was going on. It didn’t take long to reach Corleone, a nondescript town with beige colored three and four-story apartment buildings, narrow streets with traffic and honking cars, various people yelling and cafés with old men eating pastries and sipping espresso. In Corleone, we visited some museums and churches, then Baldo drove through a more run-down section of town he referred to as “Bronx of Corleone” before taking us back to Salemi.

|

| Greek Ruins, Selinunte |

|

| Monreale Cathedral |

Despite its fame as the birthplace of ruthless criminals, Corleone wasn’t all that exciting, but with Baldo as our guide, our visit there was one of the most memorable day trips that summer on the island. Sicily has an incalculably rich treasure trove of historic sites, and I was lucky enough to visit the magnificent Greek temples of Agrigento and Selinunte and the Greek Amphitheatre at Segesta. Equally breathtaking was the Arab-Norman Cathedral at Monreale and the ornate, yet neglected Baroque facades in the old city of Palermo. I loved Sicily’s chaotic capital, especially Palermo’s street markets. The markets were smelly, loud, and crowded; stands with tables piled high with seafood, meats and fruits that filled the tiny, winding streets of the decrepit old city.

|

| Palermo's Vucciria Market |

When I returned to California, the sights, smells and sounds of Sicily remained vivid in my memory and I immediately began plotting my return to that island in the Mediterranean. I imagined meeting a beautiful woman and spending my summer nights strolling down the streets of one of the island’s seaside towns, which were so full of life in the evenings. This fantasy, of traveling to a faraway land and becoming a different person, had a strong appeal to me at that time in my life. At age 19, I found myself having to make enormous decisions that would determine the course of my life and the expectations that everyone had of me as this perfect, model student. Like many 19 year olds, I was certainly not a model of responsibility: I chose to escape, whether it was through shots of gin before a party or by seeking adventures in distant lands. I returned to Sicily the following summer to work on the archaeological excavation at Monte Polizzo again. After that I studied abroad in Turkey for a year, and then worked on another dig. Eventually and reluctantly, I returned to the US to finish my degree.

Afterword

It’s easy to tell stories about travel and to write about it too. Travel is exciting, and fun, and full of new sensory experiences to describe to all who will listen. But just as I found out when I returned from Sicily and then from Turkey, most people don’t want to hear about how awesome it was to eat pizza on the piazza in Napoli; or swim through a sea cave in the Mediterranean, or about how this funny, short Sicilian guy named Baldo started calling me El Lupo and then took us on a trip to Corleone. Being able to travel is an enormous privilege. Even though returning home can be painfully isolating and dislocating, if I had enough vacation days saved up at work, I would travel in a second. Maybe not to Corleone though.

Going forward, I want to put together a longer piece out of shorter posts I did a few years ago while I was working at a rice farm. I did some of my best writing during that time and it was a challenging and illuminating experience that I still think about a lot. I also want to continue to improve as a writer, and am looking into taking some classes. Writing has always been very important to me and I want to see where I can go with it during this time of transition in my life. Thanks to everyone who has been reading, please leave a comment and keep in touch.

Comments